“The first time I set foot aboard the Yamato, I remember looking up at the bridge in awe — it towered over us like a skyscraper,” says 95 year old Hiro Kazushi, who in August 1941 joined the legendary battleship’s first crew. The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) officially commissioned Yamato that December.

Designed as a “quality over quantity” response to the numerical advantage of the US Pacific Fleet, the Yamato Class Battleships packed muscle like nothing on the water before or since. But with a price tag of around $8 billion modern USD, the IJN only commissioned two — Yamato, and her sister ship Musashi. (A third, Shinano, was converted into an aircraft carrier during production.)

At the time, the price of the Yamato was enough to feed Issen Yoshoku (the precursor to Hiroshima Prefecture’s famed okonomiyaki) to the entire population of Japan every day for a year.

The Navy’s Big Secret

To help preserve the hoped-for tactical advantage of Yamato, the IJN built her at the Kure Naval Yard in complete secrecy.

Well, almost complete.

“Yamato’s construction was top secret,” explains Kazushi, “but most people in Kure worked in the naval shipyard and no doubt talked about it with their families.” Despite swearing the building team to secrecy, comparing them with their photos on entry and exit, and placing a wooden fence around the dock to screen construction, probably half the town knew about the Navy’s “big secret.”

And big it most certainly was.

The Yamato was around the same length as the RMS Titanic, only wider, heavier, faster, and packed with cannon shells instead of chandeliers.

At 460mm, her “Type 94” main guns remain the largest ever mounted on a warship. The triple-barreled turrets which housed them each weighed more than an entire Fleet Destroyer of the era, and could rain shells weighing as much as a midsize car onto targets 32km away.

Her four secondary cannons, measuring 155mm each, matched the biggest naval caliber in use today — and that’s not counting the other 160 or so guns bristling from her decks.

Yamato’s armor alone weighed nearly half as much as the Titanic.

Eve of War

As the youngest of three siblings, Kazushi had to make his own way in the world.

“In those days in Japan,” he says, “the first born son inherited everything, and everyone else had to shift for themselves.” For daughters that meant marriage, and for the sons, it often meant traveling to Tokyo or Osaka for work.

It was while grappling with this question that Kazushi noticed a retired navy gentleman in the neighboring village. “He rode a bicycle, and had this great big German Shepherd (both rare at the time), while other people were crawling around in their rice fields.”

Inspired by this image of easy living, in 1940 Kazushi joined the Imperial Japanese Navy at age 16.

“Just my luck,” he grunts, “the Pacific War broke out the next year.”

After training, Kazushi served as Signalman for four months aboard the cruiser Kako before transferring to Yamato — his home for the next two years.

“There were some 3,000 of us aboard, and we all had our own duty,” he explains. As ship’s Signalman, he sent messages via flaghoist, visual morse code, and flag semaphore.

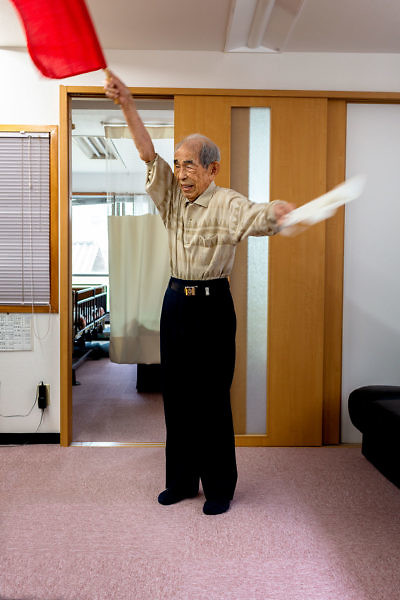

“Even after 70 years, I’ve never forgotten,” he says proudly. Then, producing a pair of red and white semaphore flags, he stands and moves them through a series of fixed positions — signaling the word “YAMATO.” Despite his venerable age, the vigorous movements come as naturally as breathing, evincing a lifetime of practice and discipline.

And life aboard Yamato was all about discipline.

Navy Spirit

“‘Haya meshi, haya guso, haya jitaku’ (eat fast, shit fast, prepare fast),” says Kazushi, reciting an old Navy saying. “Even today, I can’t break free from this spell.”

Because they were aboard the world’s greatest battleship, the crew of Yamato were expected to be the world’s best sailors too.

“It was so hard,” recalls Kazushi. “Nowadays everyone has a dream, but in those days in Japan, ‘dream’ was a foreign word. For us, it was everyday practice, everyone to their post. In the evening, the Commanding Officer would beat the ‘navy spirit’ into us with a rod of oak. My only happiness was eating, sleeping, and arriving at the port.”

Kazushi and his fellow crewmen had to be ready to rush to their posts at any moment, even in the middle of a meal. The fate of their vessel — and by extension their lives — hung in the balance.

Battle of Midway

Though “glorious on paper,” Kazushi’s two years aboard Yamato involved a lot of time anchored at port or hidden among Japan’s many islands. Partially this was to conserve fuel, a precious resource in wartime Japan. But also because Japan’s generals assumed the war would culminate in a decisive final battle, and Yamato factored among the assets they wished to save for that fight.

However, the battle they envisioned never came — though not for a lack of trying.

In 1942, Yamato became the flagship of the combined fleet when Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto came aboard. With a plan to lure the US into a trap he set sail for the Midway Atoll on May 27th.

“I wanted my family to witness our huge, majestic ship sailing east to meet the enemy,” says Kazushi. “But because our mission was secret, we couldn’t tell a soul.”

Crew member’s families may not have known about the mission, but American codebreakers did. With his fleet divided into four separate units, each too spread out to support the others, Yamamoto’s trap backfired.

Yamato was 100km from the action — over three times her maximum artillery range — when US forces ambushed and crushed the isolated ships of the IJN. With four Fleet Carriers sunk in the engagement, Japan remained on the back foot for the duration of the war.

Shore Leave

In 1943, Kazushi said farewell to Yamato and came aboard Settsu, an older battleship with a crew of 600. She served as a target ship for bomb and torpedo training. Since she wasn’t part of a fleet, Settsu remained at Etajima, an island in Hiroshima Bay near Kure, and managed to avoid combat for most of the war.

“At that time I was Petty Officer Third Class, so I got shore leave once every six days from 5pm to 10pm. I would go to my sister’s house, take a bath, and sleep on the tatami. Kure City was very busy. Even at 10pm, lots of people were there. There were three or four movie theaters in Kure City, and nightlife was always hopping. I wondered if the people ever slept.”

Eventually, his sister and her family moved to Takehara to escape the bombings which grew frequent in early 1945. “Thanks to that, they lived through the war,” says Kazushi. “But my aunt’s house downtown (near today’s City Hall) was completely destroyed.”

During an air raid on July 24th, a detachment of 30 planes attacked Settsu. A bomb struck her deck, killing two crewmen, and several near misses damaged her hull. After she started taking on water, her captain ran her aground on Etajima to avoid sinking. She never sailed again.

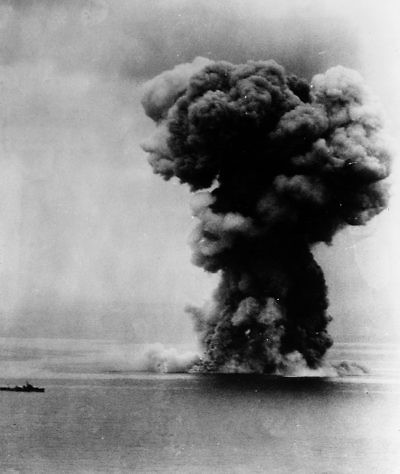

As for the Yamato, in April 1945 she embarked on a one-way mission to beach herself at Okinawa and fight the invading Allied Forces until destroyed. US codebreakers intercepted her instructions, and on April 7th, Yamato sank beneath a swarm of 400 US warplanes.

Of her 3,332 crew members, 276 survived.

“My Life was Spared”

Kazushi remained on Etajima for the rest of the war — likely one of the reasons he survived. Meanwhile, US air raids destroyed around 120 Japanese cities, Kure among them.

“I remember delivering secret papers to the Kure Naval Office about a week before the war ended,” says Kazushi. “Kure was burned to ashes. I saw the old grandmother next door to my sister’s house all burned up, her body black, tiny, and smoking.

“Then one morning on Etajima I saw a flash like lightning,” he recalls. “I thought the army munitions warehouse in Hiroshima exploded, but my Commanding Officer said it must have been a new type of bomb. We climbed up a hill and saw an enormous cloud spreading through the sky.”

The war ended nine days later on August 15th.

“Many people felt mortified that we’d lost,” says Kazushi, “but for me, it came as a relief. I’m probably not supposed to say it, but in all honesty, when I heard the war was over, I thought, ‘Because of this, my life was spared…’”

“The Best War is No War”

After the war, Kazushi worked as a minesweeper cleaning up American mines in the Seto Inland Sea, and later performed similar duties on behalf of US forces during the Korean War. Today, he leads Battleship Yamato Society, a group of former Yamato crew, most of whom served before its fateful final mission.

“I don’t really talk about it with the other members,” says Kazushi, “but I believe my days aboard Yamato formed the foundation of my life.”

But his experience in conflict has only heightened his appreciation of peace.

“The best war is no war,” he says. “Today Japan is such a peaceful country that any unimportant thing can become front page news — the other day I saw a headline about wild boars in the countryside. I’m so thankful for lasting peace in Japan. I take a bath at 3pm every day, look out the window and think, ‘My god, it’s peaceful.’ I’m deeply grateful for this. At 95 years, I’ve lived a long life, but I want to live a little bit longer.”

When asked what he’d like to tell young people about the Yamato, Kazushi merely smiles.

“Nothing really. We live in the era of guided missiles, not cannon shells. Telling people about Yamato is like talking about the Warring States Period. It was a time of war long ago.”